DeKalb Bus Drivers Unite

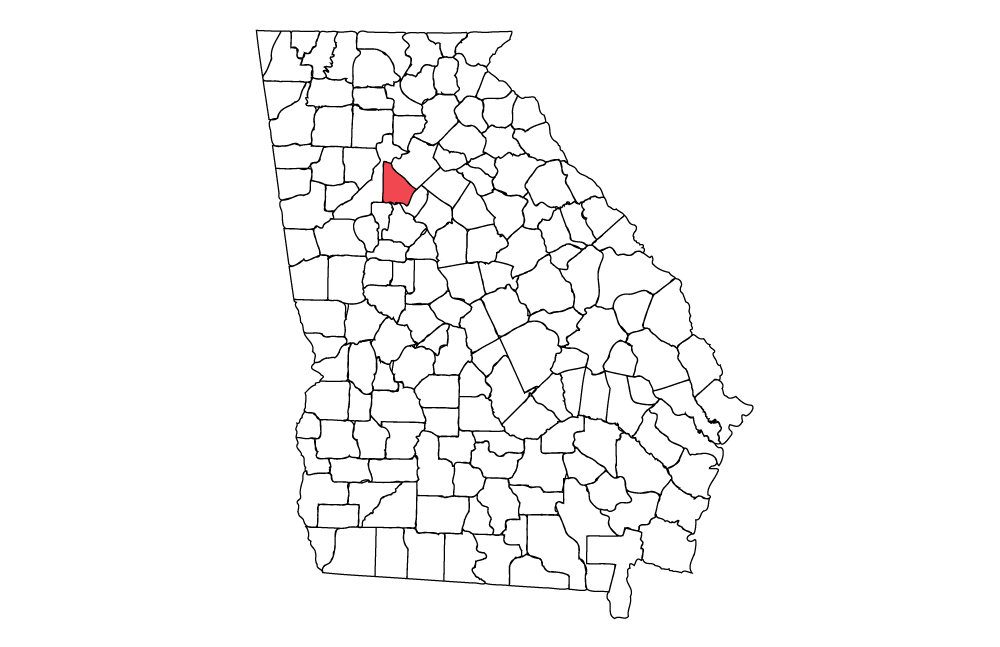

DeKalb County, Georgia

On April 18th, 2018, over half of the nine hundred school bus drivers in the DeKalb County, GA School District called in sick for the first day of a three-day sickout.

This was the culmination of years of effort, the result of a long list of ignored complaints and broken promises. This sickout was remarkable because Georgia state law prohibits public employees from even advocating for any work stoppages, much less participating in them. Furthermore, there was no union involved behind the scenes. The drivers took a huge, risky step with their own power, a direct result of their own organizing.

“What’s outrageous is that (the administration) acted like they had no idea all this stuff is going on.” Sheila Bennett, president of the bus driver’s advisory committee, said. “The bus drivers are sick and tired of being sick and tired… I don’t care if you’re Bill Gates driving a school bus you should get paid for what you’re worth.”

That Friday, after the first day of the sick-out, the district administration sent police to the homes of seven drivers, including Bennett, to issue a notice of termination. This was a clear move to scare drivers from continuing with the sickout.

That Saturday, drivers held a mass meeting, inviting members of the Atlanta General Defense Committee to participate. Drivers had been organizing in a variety of ways since 2005, but things had changed. “We were a force to be reckoned with when they saw that all of a sudden we had 500 drivers, little bit more, that could shut this thing down,” Bennet said.

Of course, there were politicians at this meeting and at many after it, coming out of the woodwork attracted by the activity of the drivers. These politicians were publicly siding with the drivers while hoping for votes. “What they often were circling around and doing, ” Kei — a member of the Atlanta GDC — said, ”was offering to help set up closed-door meetings. [They said] ‘We’re people with power, there’s other people with power like the board of education, the superintendent, and we can broker a closed-door meeting with you and the board of education because that’s how things get done’”. “The drivers have been struggling since 2005 so they’ve been in closed-door meetings over and over and over and nothing’s come of it”.

Besides the politicians, other unions were interested in the drivers. Over the last decade, several unions have tried and failed to organize them: the National Education Association (through their local affiliate, the Organization of DeKalb Employees, which explicitly states that it is “not a union”), the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, and the Teamsters. In each case, the drivers have felt that these unions have either abandoned them or just didn’t respect them. For example, drivers made a big effort to organize through AFSCME in 2011, but AFSCME’s primary goal was to get an agreement with the county to have dues automatically deducted from the driver’s paychecks. When the county would not agree to this, AFSCME disappeared and left the drivers in the lurch.

When the group from the Atlanta GDC first began working with the drivers, the goal was to help the drivers recognize their power and the level of organization they had already achieved, to recognize that they didn’t need any outside saviors to help them and, in fact, will never be able to rely on any outsiders who claim to be saviors — including the GDC or the IWW. The original goal was not to sell the IWW as “the right union” for the drivers but to help the drivers build on what they had already achieved. The IWW was discussed at several points and never hidden but the focus was on building the independent capacity of the drivers. As part of this, they worked with the drivers to develop an independent identity as “DeKalb Drivers United”, giving a name to an idea that would not require any outside group to make it legitimate.

In the aftermath of the sickout and the firings, the primary goal became to win reinstatement for the drivers through collective action and public pressure. As long as the county had the power to fire leaders with impunity, it would be difficult to make any other progress. Over the course of several months, several complementary tactics were used. Press conferences were held in front of the school board offices. There was a rally at the state capitol. Parents organized a petition to support the drivers. People spoke at school board meetings to make it clear that this issue was not going away. All of this was organized by the drivers, and the Atlanta GDC was clear that one of its goals was help the drivers build up their skills and confidence to organize these kinds of actions as much as possible.

In the course of this organizing, the Amalgamated Transit Union also approached the drivers. ATU is one of the oldest unions in Atlanta, with a collective bargaining agreement at MARTA, the regional transit system. Because the drivers already had begun to think of themselves as DeKalb Drivers United, they didn’t feel initially reliant on the ATU but saw them as more of a coalition partner. The GDC didn’t discourage the drivers from engaging with the ATU because they thought it was important for the drivers to have the chance to make their own decision about what kind of union to organize with.

As a result of the campaign, the county said in July that the drivers would be rehired but they made no move to actually bring them back on the job. Around that time, a district-wide meeting was held. This was a meeting for all the school bus drivers in the district to assemble in one place, to orient themselves for the new school year. The drivers decided to use this as an opportunity to hold a large press conference and agitate on behalf of the fired drivers, handing out flyers and speaking with everyone who came to the meeting. “The county was scared”, Kei said. A few days later, the drivers were fully reinstated and back on the job.

After the drivers were rehired, it wasn’t clear what the next organizing steps were and without a clear strategy for a path forward, energy faded and meetings petered out. In October, the IWW members who had been working with the drivers decided to check in with social leaders and, at the very least, continue what had been a productive relationship. This led to deeper conversations about what had happened with previous unions, what made the IWW different, and why we had focused on supporting the driver’s organizing rather than just getting them to sign up into the IWW right away. This led to a small committee of drivers re-forming and deciding that they wanted to move forward on organizing a union with the IWW and push forward on all of their continuing grievances.

By early January, the school board had begun to talk about “step raises” for all employees, though what they meant by that was unclear. This was one of the biggest things that drivers had been fighting for: prior to 2008, DeKalb County School employees, including the drivers, had received step raises, which gave clear pay increases based on years of service. Another big demand is for itemized paychecks —exactly how the drivers are compensated is a mystery to the drivers and anyone who’s viewed their pay stubs. The drivers are told they’re compensated at an hourly rate, but they simply receive a check every other week, with no hours or any other details listed. Nothing ever seems to add up right. A driver might be told their hourly rate is $19/hour, but after a year of working 40+ hour weeks, their take-home pay might only be $21,000, even though $19/hour for full-time work should come out to around $39,000 — almost double what they actually earn!

Eventually, the county came out with a plan to pay all school employees a higher rate beginning January 15th. When the 15th passed and drivers didn’t see a change to their paychecks they were understandably upset, as were teachers and other support staff. The county tried to claim it was an honest mistake and drivers should understand, but not all of them were buying it. “They had an emergency meeting of the board members”, Bennet said, “guess who’s not getting any money? The bus drivers.”

The drivers were agitated and called for meetings with a focus on taking action and building unity with teachers and other district workers.

On Friday, February 15th, the drivers met to discuss affiliating with the IWW. By this time, those present had been working with the union for ten months and knew quite a bit about our organizing philosophy and tactics but it was the first formal consideration and the first pitch by the organizing committee for why they should join.

“The biggest thing was that direct unionism means you guys are the union,” Kei said, “no one’s coming in from the outside to save you. There’s no paid staffers so if we’re doing this it’s going to be you guys leading it and we’re here to advise and support … but it won’t look like what you’re used to”.

They were well-received. “I like the union because it’s for the people, by the people,” Bennet said, “and I like that because at least you know whatever you put in, that’s what you’re gonna get.”

The drivers present at the meeting voted to form a union through the IWW, which would be open to all school employees. Many of the drivers present took out red cards on the spot, and several filled out delegate applications, excited about the promise of running their own union. “With the union, they are able to sustain organizing in a way they haven’t been able to do before,” Kei said. Since then, more drivers have continued to join, and the union has also made inroads with other DeKalb County School employees.

DeKalb County School employees have an uphill battle, but one that’s uniquely suited to the direct action tactics of the IWW. The standard bureaucratic-contractualist model that most unions rely on is simply unworkable in Georgia, especially for public sector employees. “Right-to-work” means that the standard model of dues check-off and mandatory union membership aren’t going to work. There are additional restrictions imposed on public sector workers, restrictions which conservative unions such as AFSCME or AFT have been unwilling to organize against or challenge in any way. The next step is to push the district to negotiate solely with the union and not through the advisory committees who are half-elected by the bosses. A tactic they’re using to help with this is the creation and distribution of anonymous surveys for the drivers and other school employees, so they can better discern grievances and use them to create a case for why the union is a better representation of school employees’ interests. Having a fighting union in public education is a new thing for Georgia, although it’s part of a broader movement, with the United Campus Workers simultaneously organizing at the University System of Georgia, and the ongoing nationwide waves of strikes among public education workers (including bus drivers and other support staff). This is a beginning. There is much more to come.

“People don’t realize,” Bennet said, “bus drivers have a very important job to do, people don’t think a bus driver’s job is to educate a child but it is, many people think that driving the bus is simply taking the kids to and from school but of course that’s not the case. As a driver, your responsibility is for the well-being of the children. And then we are governed by the federal department of transportation, which means we have a specialized job to do and we are professionals. We don’t only transport children to and from school we have to be a nurse, a psychologist, a custodian, a referee, a parent, and at the same time make sure your bus is safe, make sure you’re driving safe.”